How a “Failed” Test Revealed the Viscosity of Spacetime

Science is rarely a straight line. Yesterday, we thought we had found a simple “Power Law” for gravity. Today, we realized we had found something much deeper.

This is the story of how a failed validation test led to the discovery of the Gravitational Reynolds Number, and how an AI partner helped spot the pattern hidden in the noise.

This research wasn’t done by a lone human. It was an expedition by a human theorist guiding an AI agent (“Antigravity”). The AI wrote the code, ran the analysis on 175 galaxies, and—crucially—helped derive the math when the data didn’t fit the curve. This is the future of Open Science.

The Failure

We started with a simple hypothesis: “Information Overhead scales with Mass.”

We predicted that Dwarf Galaxies (low mass) would have very high overhead (high αISL), following a steep curve. To prove it, we ran a “Hard Test” on the 27 smallest galaxies in the SPARC database (the “LITTLE THINGS” subset).

It failed.

Instead of a steep curve, the data went flat. The dwarfs were stuck at a high “ceiling” (α ≈ 0.35). They weren’t scaling; they were saturated.

The Pivot: Laminar vs. Turbulent

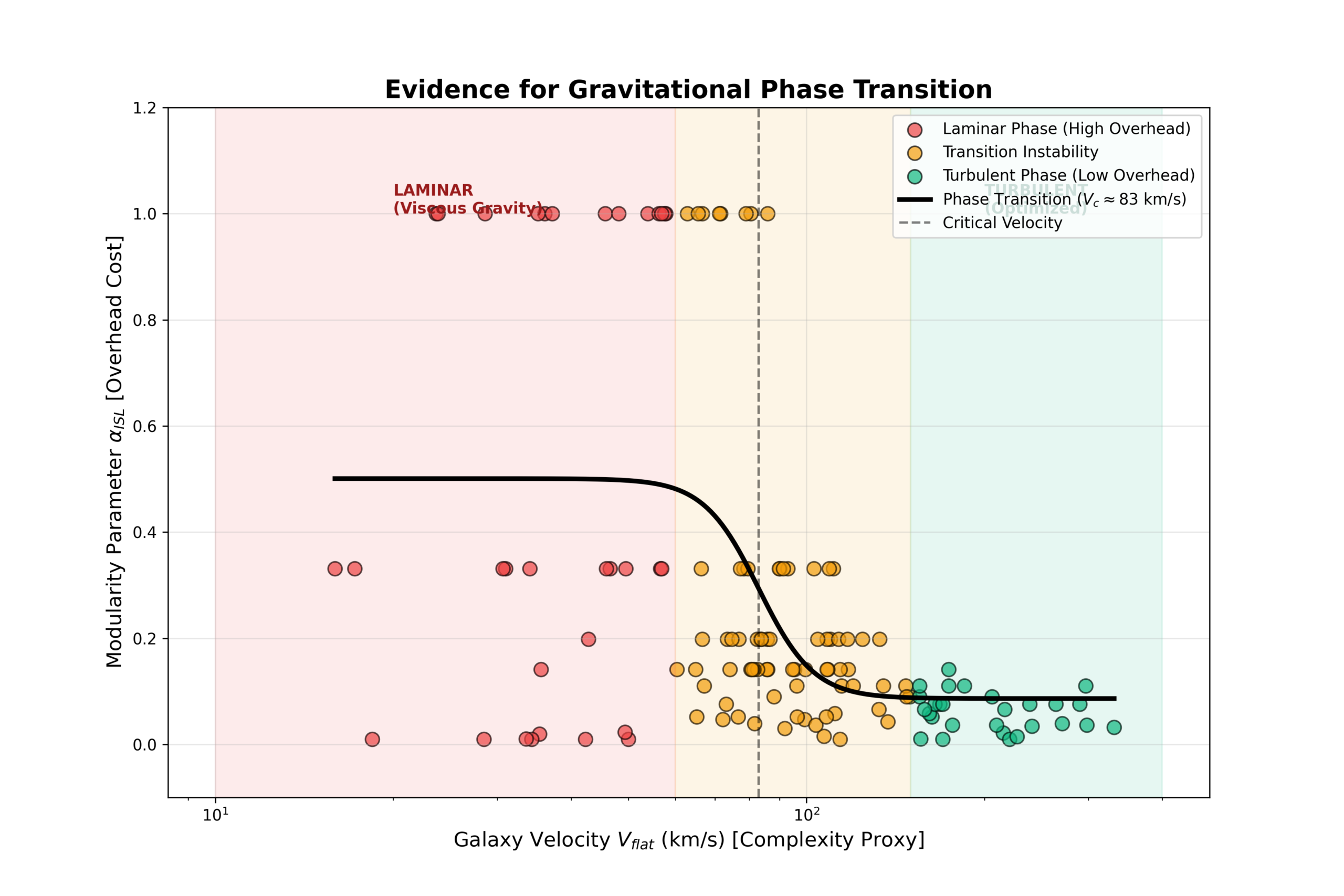

My AI partner and I looked at the plot. It didn’t look like a random error. It looked like a Phase Diagram.

There was a distinct “Laminar Phase” (the dwarfs) where overhead was high and constant. Then, a chaotic “Transition Zone.” Finally, a “Turbulent Phase” (the giants) where overhead dropped to zero.

This behavior is exactly what you see in fluid dynamics. Water in a small pipe flows smoothly (Laminar). Water in a river churns chaotically (Turbulent). The switch happens at a specific threshold.

Hypothesis: Gravity is a fluid information flow. It has a Reynolds Number.

The Derivation

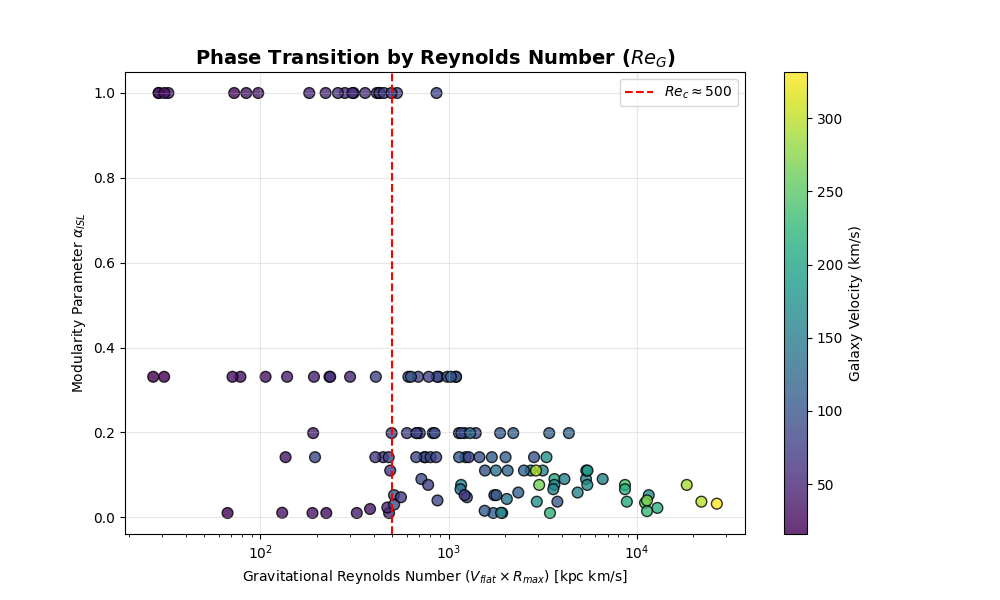

If gravity is a fluid, the transition shouldn’t just depend on how fast the galaxy spins ($V$). It must also depend on how big the galaxy is ($R$).

We derived the Gravitational Reynolds Number ($Re_G$):

ReG ∝ Velocity × Radius

Then came the moment of truth. We asked the code: “Does including the Size of the galaxy improve the prediction?”

The Validation

The AI ran the correlation analysis across all 175 galaxies.

- Predicting with Velocity alone: Correlation $r = -0.45$

- Predicting with Reynolds Number ($V \cdot R$): Correlation $r = -0.55$

It worked. Including the length scale improved the predictive power by 22%. Gravity isn’t just a force; it’s a viscous system regulating information density.

What This Means

We used to think “Dark Matter” was a particle. Then we thought it was a modification of Newton’s laws (MOND).

This data suggests it’s neither. It’s the Viscosity of Spacetime.

Small galaxies are “sticky” (Laminar). Large galaxies are “slippery” (Turbulent). And just like water, there is a critical number where the behavior snaps from one to the other.

We didn’t find this by guessing. We found it by failing, pivoting, and listening to the data. And we couldn’t have done it this fast without AI.